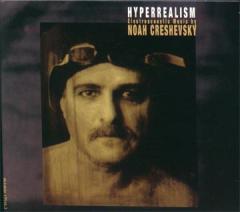

NOAH CRESHEVSKY / Hyperrealism

"I do not exaggerate when I say that I have never heard anything like Noah Creshevsky's music before - though I can hear the ghost of Berio lurking in there. This music is uncompromising. It has a robust sense of humor." - American Record Guide

Hyperrealism is an electroacoustic musical language constructed from sounds that are found in our shared environment ("realism"), handled in ways that are somehow exaggerated or excessive ("hyper").

Fundamental to hyperrealism is the expansion of the sound palettes from which music is made. Developments in technology and transformations in social and economic realities have made it possible for composers to incorporate the sounds of the entire world into their music. Essential to the concept of hyperrealism is that its sounds are generally of natural origin, and that they remain sufficiently unprocessed so that their origin is perceived by the listener as being "natural." Since the sounds of our environment vary from year to year, generation to generation, and culture to culture, it is impossible to isolate a definitive encyclopedia of "natural" sounds, but there are a great many sounds that are familiar to nearly all of us. These are the most basic building blocks in the formation of a shared (if temporary) collective sonic reality. Hyperrealism celebrates bounty, either by the extravagant treatment of limited sound palettes or by assembling and manipulating substantially extended palettes.

TRACK LIST

Canto di Malavita (6:37)

Jacob's Ladder (7:52)

Vol-au-vent (5:10)

Hoodlum Priest (6:05) (vocal samples: Thomas Buckner; electric guitar samples: Marco Oppedisano)

Novella (7:29)

Ossi di morte (11:29)

Jubilate (6:23) (voice & vocal samples: Thomas Buckner)

Born Again (5:10)

REVIEWS

If I could play you the CD I'm listening to right now, I'd tell you it was by the latest 22-year-old sampling hotshot, some kid who dropped out of college because he was having too much fun subverting his laptop audio software. And you'd believe me. But I'd be pulling your leg. Then, if I could have the real composer walk in, you'd be astonished to see that Noah Creshevsky is no baggy-jeaned club DJ, but a quiet and reclusive retired Brooklyn College professor. Because there is nothing sedate or self-important about the crazy Alice in Wonderland sonic mayhem that Creshevsky has been gleefully creating for the last 30 years, even back when he had to use reel-to-reel tape to do it, when touch-key sampling was hardly even a futuristic dream.

The CD's apt title is Hyperrealism (Mutable Music), and in brief liner notes Creshevsky explains the philosophy of his own personal ism. On one hand, he creates virtual "superperformers" by using the sounds of traditional instruments pushed past the capacities of human performance. (An early disc on Centaur was called Man and Superman.) He also, like many others these days, likes to incorporate the sounds of everyday life as musical materials, and he insists on these sounds being "natural," recognizable, even included for their cultural resonance. Other sampler composers do as much: Charles Amirkhanian paints luxurious sonic landscapes from environmental sounds; Carl Stone reconfigures recorded sounds in pop rhythms. But Creshevsky slices his sounds into thin strips and ripples through arpeggios on them like a virtuoso pianist of the absurd, and the results are truly disorienting.

Canto di Malavita, for instance, weaves a melody from sitar glissandos, lightning-fast piano scales, a rocker's drum lick, a string orchestra pizzicato, and sometimes the middle third of a quick note from an opera singer. And that's the problem with even trying to describe this music: Many of these slices of sound zip by too fast to cross the threshold of recognition. I think that's Rachmaninoff's Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini in there, but it's difficult to tell from just a dozen milliseconds. The old game of "Name that piece in one note or less" takes on new meaning as Creshevsky whips between different cultures several times within a beat. It's as though Conlon Nancarrow had had, not just the keys of a player piano, but a huge, multicultural jukebox with split-second control.

Perhaps you've already picked up the one clue to Creshevsky's age: His sonic references do tend to veer more toward classical than pop. Ossi di morte sounds like someone dropped and shattered an opera, then glued the tiny shards back together in a completely wrong order, complete with audience coughs—or perhaps they're dying soprano gasps? Two pieces involve Downtown baritone Thomas Buckner, who a couple of times is allowed to finish an entire unsliced phrase. It sharpens the sense of absurdity, in fact, that there is always a strong melodic element present, or rather meta-melodic. This is info-overload music, but not chaotic, not a sonic free-for-all. Each piece limits itself to a certain group of sound worlds, building a distinct atmosphere from incongruously mixed elements that blur together from sheer speed of alternation.

That's not to diminish the extreme perceptual challenge Creshevsky poses. The jumble of mouth sounds, guitar licks, and interrupted Tchaikovsky phrases, the abrupt intercutting, and the meta-organization into musically meaningful beats and measures result in a layered cognitive dissonance in which the familiar, the absurd, the jarring, and the melodic jostle for dominance. You can recognize these pieces, you can delight in them, but I can't imagine any amount of exposure ever getting me used to them.

Not for composer Noah Creshevsky is the original ethos of electroacoustic music, where the source material must be bent far enough to obscure its origin thoroughly. Rather appropriately for a student of Nadia Boulanger and Luciano Berio, both of whom were preachers of evolution rather than revolution, Creshevsky in fact does just the opposite. This jumble of sound samples culls recognisable (if not immediately placeable) quotes from the operatic, instrumental and orchestral repertoire, as well as some original sound samples, into an entirely new sonic landscape. This 'hyperrealism', which Creshevsky defines as 'an expansion of the sound palettes from which music is made', relies entirely on identifying with the music both in its original as well as its transformed context.

These are not, however, the sonic collages of Karlheinz Stockhausen or John Zorn, where the point is to find the most shocking juxtaposition. Instead, Creshevsky looks for an inner consistency. Sustained pitches will suddenly switch voicings; an instrumental flourish beginning in one instrument may suddenly continue with another. Old fragments may emerge in new multitextured melodies, such as the electronicised hockets in Jubilate. The results range from the surprisingly contemplative choral collage of Jacob's Ladder to the last gasps of breath cleverly punctuating Ossi di morte. Throughout this collection is an impressive guiding vision that holds even the most diverse ideas together, a sonic vocabulary where even the most highly processed sounds still show their roots. The results ae entirely the product of Creshevsky's private world, but he makes it clear that the rest of us are invited.

American Record Guide, May/June 2004

I do not exaggerate when I say that I have never heard anything like Noah Creshevsky's music before - though I can hear the ghost of Berio lurking in there. This music is uncompromising. It has a robust sense of humor. All of it involves radical crosscutting between diverse sound samples. The edges between samples are deliberately crisp. There's very little layering or blending. Its vertical transparency balances its horizontal density.

The ingredients are a recipe for chaos, but Creshevsky cooks them to taste. How? Despite all of the sampling, the crosscuttinghas a quasi-regular rhythmic structure. This way he is able to weave together several strands of sampled music (ranging from sitar to banjo and from Beethoven to bel canto) while maintaining their stylistic identities. A segment from each strand of sampled sounds falls on a different beat; the ear connects the dots. It might strike some as gimmicky, but after listening to it several times I'll maintain that Creshevsy's sound art is carefully crafted and sensitively musical. The adjacent samples are well chosen to draw out coections between them. Creshevsky calls his style hyperrealism. I'd call it hyper-sampling. Whatever you call it, if you're up for an aural adventure, here's your ticket.