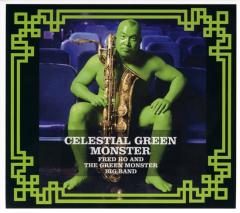

Fred Ho and The Green Monster Big Band - Celestial Green Monster

The Green Monster Big Band: Fred Ho (leader/baritone sax); Bobby Zankel, Jim Hobbs (alto sax); Hafez Modirzadeh, Salim Washington (tenor sax); Stanton Davis, Brian Kilpatrick, Amir Elsaffar (trumpet); Taylor Ho Bynum (cornet); Robert Pilkington, Marty Wehner, Richard Harper (trombone); Earl MacIntyre, David Harris (contrabass trombone); Art Hirahara (piano, electronic keyboard); Wes Brown (electric and acoustic bass); Royal Hartigan (drum set)

Guest Artists on In A Gadda Da Vida: Abraham Gomez-Delgado and Haleh Abghari (vocals); Mary Halvorson (electric guitar)

On Celestial Green Monster, Fred Ho and the Green Monster Big Band - assembled from Ho¹s favorite musicians with whom he had the pleasure and honor to work with since embarking upon a professional career in music in the 1980s - perform both original compositions by Ho (Liberation Genesis; Blues to the Freedom Fighters; The Struggle for a New World Suite) as well as arrangements of two pop culture classics (Spiderman Theme; In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida).

The quintessential American orchestra is not the symphony, but the big band. Retaining the essential features of swing and African-descended rhythmic vitality and complexity, improvisation (both individual and collective) with sophisticated compositional imagination, elasticity and experimentation with timbre and harmony, expansive and epic themes, the big band makes for as much a "joyful noise" as the ubiquitous small band. Though the composer/arranger may start with sketches and minimally notated material, the opportunity and challenge for a broader and more extensive palette of orchestral voicing, contrapuntal techniques (both melodically and rhythmically), and magnified excitement, intensity, energy and explosive dynamic range ("from a whisper to a scream") continually make for the big band form an ideal vehicle of serious extended composition. Over the years, Mr. Ho¹s influences in big band writing have included composer/arrangers such as Duke Ellington, Thad Jones, Count Basie, Sun Ra, RoMas (Romulus Franceschini and Calvin Massey), Toshiko Akiyoshi, Charles Tolliver, Don Ellis, Frank Foster, Melba Liston, Shorty Rogers, Lalo Schifrin, Charles Mingus, and Tadd Dameron, among others. The popular "jazz-rock" horn bands also contributed mightily to Ho¹s musical consciousness, including Chicago Transit Authority, Blood, Sweat and Tears, Tower of Power, Azteca, Malo, Flock, Cold Blood; as well as black funk and soul bands such as Mandrill, Crown Heights Affair, Brass Construction, Earth, Wind and Fire, The Pyramids, and Kool and the Gang. And his oeuvre also included the blazing salsa bands led by Eddie Palmieri, Mongo Santamaria, Ray Barretto, Bobby Paunetto, Willie Colon, and Celia Cruz. All of this is reflected in this amazing and amazingly joyful recording.

TRACK LIST

Spiderman Theme (2:17)

In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida:

Blue Planet, My Love (6:50)

Journey to the Dark Heart, Enter the Serpents of Stratification (2:44)

Mastodon, My Friend (0:44)

Where Angels, Mastodons, Sabertooths and Whales Fear to Tread (1:27)

The Tipping Point of No Return (4:11)

Liberation Genesis (6:53)

Blues to the Freedom Fighter (9:54)

The Struggle for a New World Suite:

Part of the Solution, NOT Part of the Problem (2:03)

Original, Organic and African (9:29)

Battleground Earth Blues (6:14)

Patience, Passion and Praxis (3:07)

Up Against the Wall You *$%&@# Gods of Corporate Profit! (1:37)

Paper Tigers are Real Scaredy Cats (6:28)

Guerillas Gone Wild (9:13)

REVIEWS

Bill Shoemaker, Point of Departure

Facing long odds to survive after the reappearance of advanced colo-rectal cancer in 2007, Fred Ho initiated a big band project, an implicit summation of his work as a composer. For the repertoire, he dug deep into his book, finding two pieces he wrote while at Harvard in the mid 1970s, snapshots of a budding sensibility fusing jazz and revolutionary politics. A suite penned during the early rounds of his cancer treatment in 2006 was the logical choice to represent his recent, perhaps last articulations of the social justice issues that sharpened his art over the decades. Had he rounded out the program with similarly inspired works, the resulting album would have reinforced Ho's cred as a revolutionary, albeit one that occasionally appears on album covers in the buff.

But, he didn't. Instead, he arranged two pieces of music so far afield from his wheelhouse to inflict a standing 8-count of cognitive dissonance on his long-time listeners: the theme from the Spiderman cartoon series and "In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida." Historically, Ho has had no use for kitsch, so the question is begged: Why? Ho states in his booklet essay that grew up on the stuff – simple as that. Yet, in a somewhat convoluted way, the inclusion of his arrangements on Celestial Green Monster is consonant with the traditional liberation agenda of his music.

Granted, cartoon themes and rock anthems are easily repudiated as mass media manipulations, but they, with a throng of other similar materials, are just as embedded in the subconscious of the critically minded American as those on the tread wheel or at the trough. When the play button is engaged by happenstance, be it catching a glimpse of an advertisement on a passing bus or a whiff of patchouli oil in a crowd, the reaction of the former group is apt to be a cringe. The rationale and even passion of rejecting mass culture, however, is overridden by the urge for reconciliation when one is presumed to be terminally ill.

That's sufficient motivation; but there is also a case – perhaps thin – that connects these arrangements to recurring themes in Ho's music. Stan Lee's The Amazing Spiderman is the same type of trickster anti-hero portrayed in Monkey, and the webslinger's gravity-defying antics are mirrored in the astounding feats of the martial artists who performed in Voice of the Dragon. In a murky way, Iron Butterfly's hippie Eden signifies a predicate for the new humanity that Ho identifies as communism.

Additionally, Ho projects a sense of humor on Celestial Green Monster that is surprisingly rooted in television commercials, further complicating his signals. Ho's going green for the cover photography is buttressed by the booklet's reference to the "Ho ho ho" of The Jolly Green Giant, the benevolent bearer of canned vegetables for more than a half-century. Not only is this a double-edged choice given Ho's dedicated pursuit of organic farming, but because Ho has fiercely opposed ravenous corporate behavior like the serial takeovers of the grassroots Minnesota company that created the mascot, opposition that would indicate the invocation of another towering green-skinned figure of the modern American imagination: Lee's avenging The Incredible Hulk. Less prominent is the pun contained in the title of the last movement of "The Struggle for a New World Suite" – "Guerillas Gone Wild" – which plays off "Girls Gone Wild," a series of DVDs featuring breasts-baring college-aged women, whose commercials saturate dead-of-night TV. Coming from the composer of "Yes Means Yes, No Means No, Whatever She Wears, Wherever She Goes!," the title, under normal circumstances, would be puzzling, at the least.

But, Ho's situation was and remains far from normal. Skewed humor, the revisiting of formative experiences and the push for closure and validation are common responses to dire circumstances; they also lead to extraordinary, exorcising art, especially when the source materials are as pointed as those Ho covers. Subsequently, this is music not to be received in terms of how hip or post-it-all it may be, but its quality of feeling. Neither of the performances in question have the glibness that generally plagues such endeavors; rather, their straight-faced delivery is both engaging and unsettling. It would be the sonic equivalent of looking at someone's high school yearbook without it.

To this end, the crisp attack of Ho's 17-piece ensemble – a mix of long-time comrades like percussionist Royal Hartigan and tenor saxophonist Hafez Modirzadeh, veterans like trumpeter Stanton Davis and trombonist Earl MacIntyre, and younger impact players like cornetist Taylor Ho Bynum and alto saxophonist Jim Hobbs – is crucial on the Spiderman theme, particularly when the hard-charging rhythm of the main blues variant slips into the looser swing of the bridge. The brevity of the performance intensifies its punch; pianist Art Hirahara and bassist Wes Brown's use of electric instruments lend period tang, while Hobbs hands in a fierce solo.

Likewise, Ho's take on "In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida" uses period flourishes; Hirahara's organ solo and guest guitarist Mary Halverson's walk-on recall Al Kooper's modal ventures and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band's seminal "East West," respectively. But, these elements, which successfully navigate the minefield of the piece's history, are overshadowed by a few truly unexpected gems, like Haleh Abghari's Persian vocalese and similarly tinged writing for the horns.

"Liberation Genesis" ('75) and "Blues to the Freedom Fighters" ('74) may technically be considered student works, but they don't sound like it. They exude the freshness of mid-‘70s populist post-Coltrane jazz; the use of modes and minor blues would be fertile ground for contemporary exponents like Carlos Garnett or the Grubbs brothers. There are a few well-placed updating devices that Ho employs, like his unaccompanied duet with Modirzadeh that opens "Liberation." More importantly, Ho's keen improvisational reflexes in this passage and his shouting chorus on "Blues" confirm Ho still has one of the most cut and cutting baritone saxophone sounds in jazz.

Clocking in just less than forty minutes, "The Struggle for a New World Suite" is a major work in scale, scope and substance. The seven-movement work runs the gamut from strutting riffs to attenuated, silence punctuated interludes, producing frequent and pronounced pivots in its course; yet the piece never lurches from event to event, a solid measure of Ho sense of pacing, proportioning and sequencing. There's much that Ho's long-time listeners will find familiar. The way he builds energy with riffs and counter lines, unleashes riotous improvised polyphony, and give ballads iridescent shades reflects the life-long influence of Mingus, and the acknowledgement of Hemphill's innovations in these areas. It is noteworthy that the confluence of these shadows occurs in the keystone-like fourth movement, a ballad that combines searing lyricism and delicate harmonic tension, culminating in a short Ho solo that is simultaneously primal and archly sophisticated. For all of its finely crafted ensembles, however, this is still a symphony for improvisers to a substantial degree. Seventeen solos are listed in the credits for the piece, and each of them is persuasive, even though special mention should be made of Hirahara, who solos forcefully on both acoustic and electric instruments, and tenor saxophonist Salim Washington, whose roiling culminating solo confirms his status as one of the more accomplished artists ignored by the US jazz press today.

Heard from beginning to end, Celestial Green Monster is a compelling autobiographical statement, even if, musically, it can be likened to a journey from thin ice to the summit. There's bravery in this music.